A Case, Cosign, and Roll Call for Women of Color in the Arts

An essay for Sixty Inches From Center.

December 2017

Excerpt:

“We’re the only ones we can rely on to liberate ourselves…and articulate the specifics of our lives…”

– Kimberlé Crenshaw at the National Women’s Studies Association’s 2017 Annual Conference: 40 Years after Combahee: Feminist Scholars and Activists Engage the Movement for Black Lives

“…my overall concern is with black feminist creativity in general and with the manner in which, in fields like popular music, opera, and modeling, media visibility may be allowed to substitute for black female economic and political power, whereas in more politically articulate fields such as film, theatre, and TV news commentary, black feminist creativity is routinely gagged and ‘disappeared.’”

– Michele Wallace, Variations on Negation and the Heresy of Black Feminist Creativity

When I read the words of these women I’m reminded that I’m not alone in my thinking. The uneasiness or invisibility that I feel for myself and other Black women in different situations isn’t unwarranted or an emotional overreaction. It’s not my imagination playing tricks on me. Within cultural, political, and social spaces, the lack of care, commitment, and consideration for Women of Color (WoC) is often palpable, taking the form of a sticky web of presence and absence that drapes heavily over situations and conversations constantly.

When I argue for WoC to take the lead in the arts, people are compelled to start naming names. They ask, “What about [insert name of a highly visible WoC in the arts here]?” Yes, there are some–several, in fact. When listed (as I start to do later in this piece), the presence of WoC feels significant and undeniable. But as Michele Wallace argues in her essay, visibility does not equal power and it does not protect us from disappearing into the buried alcoves of history. Depending on whose hands are dealing the cards, these examples of visibility can be superficial and sometimes lack the depth to make them feel like a convincing example of our experiences and existence, or hold any sign of authenticity.

Visibility is significant, no doubt, but it’s basic. It’s the low hanging fruit and the easiest thing to do. Sometimes it’s simply tokenism for the sake of ‘good’ optics and diversity initiatives running wild and unchallenged. For example, when choosing an image for a website homepage, newsletter, or institutional Instagram feed, make sure it’s got some PoC in there as evidence that you’re inclusive. Every once in a while, put some extra marketing dollars behind that event inviting important PoC and WoC voices to the mic and the stage (and be sure to snap some photos of that beautiful Black and Brown audience that shows up for them). This is shaky evidence–too shaky to be taken as true care and inclusion.

If that’s the least that can be done, then what is the most–or at least more? More looks like the people behind cultural organizations and platforms being WoC. It can also look like WoC pushing for, making space in, and claiming leading positions at these organizations. It looks like having access to resources and opportunities to build our own organizations, institutions, and platforms from the ground up, if that’s what some WoC desire. The most looks like me no longer needing to write these words and make this case because the examples are clear and abundant, constantly growing and not discounted.

Read the full essay here...

Photo Credits, top to bottom:

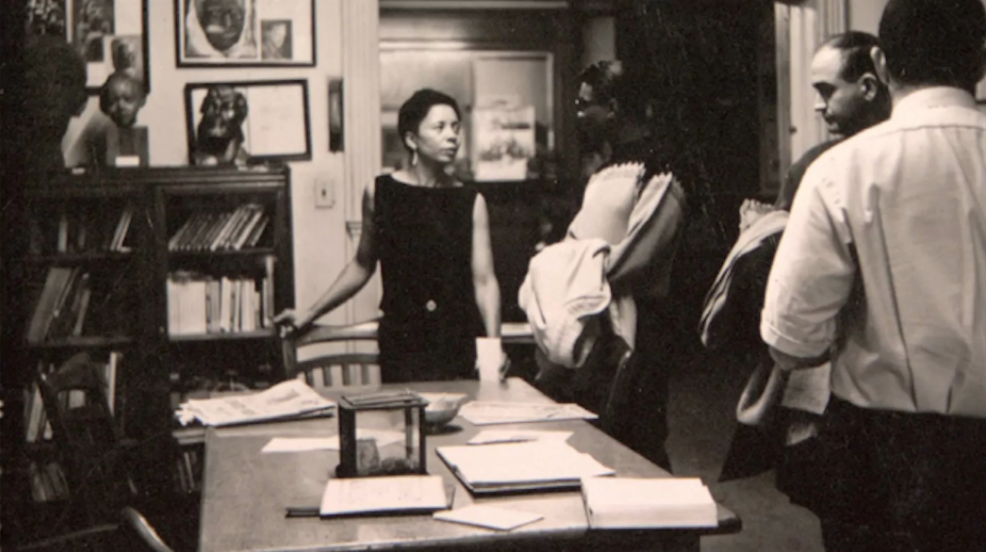

[1] Photo is takin inside of the original location of DuSable Museum on South Michigan Avenue, circa 1961. Photo courtesy of the Chicago Defender.

[2] Installation view of Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960 – 1985 at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2017. Photo by Tempestt Hazel.

[3] Installation view of We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965 – 1985 at the California African American Museum, Los Angeles, 2017. Photo by Tempestt Hazel.

[4] Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs, Faces A La Picasso, linoleum block print, circa 1968.